Since the war in Sudan erupted in 2023, more than 240,000 Sudanese refugees have fled to Libya in search of safety.

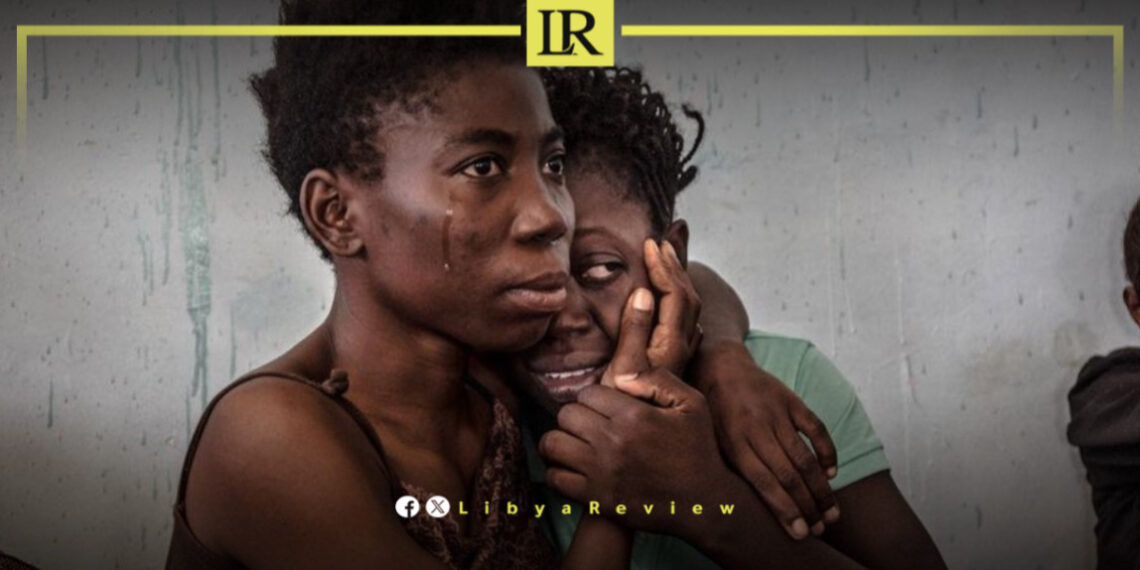

Instead of refuge, many have found themselves trapped in a cycle of unimaginable horror, facing violence, slavery, and even organ trafficking. Libya, a country already plagued by instability and lawlessness, has become one of the most dangerous places for African refugees.

With no legal protection, Sudanese migrants are at the mercy of smugglers, militias, and criminal networks that exploit their vulnerability.

Many Sudanese refugees enter Libya through Kufra, a well-known transit hub controlled by armed groups and traffickers. Instead of finding assistance, they are subjected to starvation, forced labor, and extreme brutality.

Seventeen-year-old Fareed, a refugee from Darfur, described witnessing horrifying acts, including rape and murder. He recalled seeing a young girl being attacked and left to die on the streets, only for her mother to take her body back to Sudan, saying she would rather her daughter die in the war than suffer in Libya.

The ordeal does not end there. Many refugees are sold into forced labor, forced to work under extreme conditions without pay.

Those who resist are either tortured, killed, or handed over to rival militias. Fareed described his experience in Kufra, where he was forced to collect plastic waste for recycling without any wages. When he complained, he was told that if he caused problems, he would be sold to another armed group.

He explained that many refugees are forced to fight in conflicts that are not their own, while others simply disappear. The alternative, he said, is even more terrifying—organ trafficking.

A 2021 report by the UK-based Gray Analytics revealed that Libya has become a hub for organ trafficking, where African migrants, particularly Sudanese refugees, are targeted. These victims are often sold into slavery first and then murdered for their organs, which are smuggled to buyers in the Middle East, Europe, and North America.

The testimonies of survivors confirm that this practice remains widespread, with refugees who resist forced labor often disappearing, only for their bodies to be discovered later.

For those who avoid this fate, the next step is often arrest and detention. Sudanese refugees are frequently extorted by corrupt officials, and forced to pay bribes to secure their release, only to be detained again shortly after.

Nineteen-year-old Ahmed compared his time in Libya’s detention centers to a game of snakes and ladders, where each arrest sent him back to the start. Every time he was caught, he had to pay to be freed, and the process repeated itself.

For many, the only remaining option is to risk their lives at sea. The Mediterranean remains the deadliest migration route in the world, with thousands of migrants drowning each year. Ahmed described his terrifying sea journey, explaining how the type of boat a refugee is placed in depends on how much they can pay.

Sudanese and Eritrean refugees, often with no money, are forced onto the most dangerous, overcrowded dinghies, drastically lowering their chances of survival. He said the desperation is so great that even knowing the risks, many still choose to cross, believing that drowning in the sea is better than dying in Libya.

Despite the rising numbers of Sudanese refugees arriving in Libya, there has been little international response to their suffering. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that Sudanese refugees now make up nearly three-quarters of all refugees in Libya, yet there is no coordinated effort to protect them.

Libyan authorities, already struggling with political divisions and security challenges, have neither the resources nor the will to intervene. As a result, Sudanese migrants remain trapped, unable to move forward, and unable to return home.