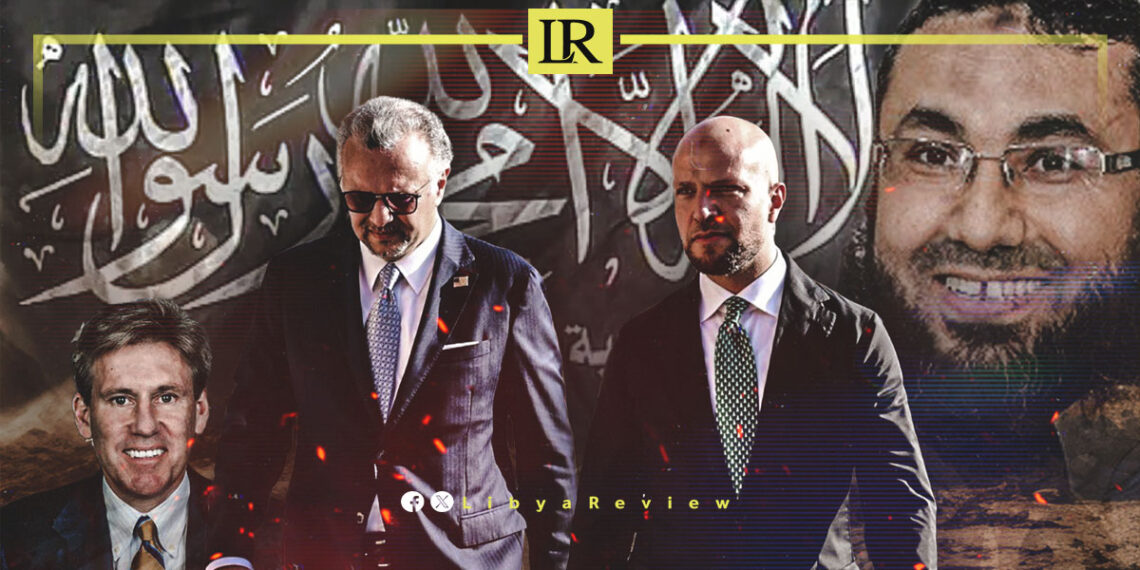

The United States recently took custody of a Libyan suspect accused of involvement in the 2012 attack on its mission in Benghazi — an assault that killed Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans and continues to shape Washington’s Libya policy more than a decade later.

Yet some of the figures who operated publicly during that same period now sit across the table from foreign officials as representatives of the Libyan state. Among them is an official whose media role at the time included televised appearances and broadcasts featuring groups later designated extremist.

In Libya, the war against armed organisations has largely faded from the battlefield, but its legacy has not disappeared from public life. Some of the personalities of that era re-emerged in government offices and diplomatic meetings, reframed not as wartime actors but as political interlocutors.

This article examines how one media figure from Benghazi’s conflict years moved from the airwaves of a divided city to the halls of government.

On many nights during 2012 and 2013, residents of Benghazi learned to recognise the sound before they even reached the window: tyres screeching to a halt, a burst of gunfire, and then silence. Within minutes, word would spread across neighbourhoods and social media: another officer, another activist, another judge had been killed in cold blood. By morning, a crowd would gather around a blood-stained pavement as security forces arrived long after the gunmen had disappeared.

Benghazi’s Killing Fields or Benghazi’s Reign of Terror

Such killings became routine. Over the following two years, hundreds of targeted assassinations were recorded across the city, alongside bombings of police stations, attacks on army units and the near-collapse of formal law enforcement. Armed groups operated checkpoints, detention sites and public offices openly, presenting themselves as protectors of the revolution while the state struggled to assert its authority. Human Rights Watch later reported that unlawful killings in Benghazi reached roughly one per day at the height of the violence According to reporting cited by Refworld, the United Nations refugee documentation database, at least 250 politically motivated assassinations were documented across eastern Libya by 2014. Journalists were also targeted; The Guardian also reported that journalists in the city were being shot and threatened amid the widening campaign of violence.

The Night the U.S. Mission Was Attacked

It was within this atmosphere in which gunmen attacked the U.S. diplomatic compound in Benghazi on September 11, 2012,, killing Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. Investigations later linked the attackers to extremist networks that were already operating publicly in the city -organisations that held press conferences, patrolled neighbourhoods and communicated directly with the public.

At the time, several Islamist armed factions operated openly in Benghazi, maintaining offices, organising patrols and holding public events. Among them was Ansar al-Sharia, a group later designated a terrorist organisation by the United States, Ansar al Sharia ran security checkpoints, provided social services and regularly addressed the public through statements and press conferences. Its members were a visible presence in parts of the city, interacting with residents and media outlets in a manner that blurred the line between militia and authority.

The Airwaves of the War

Alongside their armed presence, the groups maintained a public messaging campaign. Statements were issued regularly, announcements circulated online, and press conferences were held in front of cameras. In a city where state institutions were weak, these appearances served not only to communicate with supporters but also to project legitimacy.

During the same period, a range of Libyan broadcasters were emerging across the country, including channels such as Libya Al-Ahrar and Al-Nabaa, which covered political developments and the unfolding conflict from shifting editorial perspectives. In Benghazi, however, some local outlets went beyond reporting on armed factions and became regular venues through which those groups addressed the public directly.

A Platform on Television

Among them was Al-Nabaa television, which aired press conferences and statements by factions operating in the city during the wave of assassinations.

The coverage did not occur in isolation. At a time when many institutions were absent from public life, television remained one of the few ways residents received information about security conditions. The result was that armed groups were not only present in the streets but also present on screens, speaking directly to audiences across the city.

At the time, the station operated under a formal management structure headed by a general manager responsible for editorial direction and broadcast output.

Archived broadcasts from the period show how armed factions active in Benghazi communicated with the public through televised appearances as well as battlefield activity. In one interview, Walid al-Lafi, then the general manager of Al-Nabaa television, relayed what he described as information from sources within the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council about a suicide operation in the Al-Laithy district, saying the group had “carried out a martyrdom operation” that caused casualties among opposing forces. (Minutes 12:46-14:06)

In other appearances, the terminology used on air reflected the political language of the conflict. During a televised discussion, al-Lafi said the channel would not “yield to pressure to describe the revolutionaries as terrorists,” framing the fighters within the narrative of the February uprising. In a separate segment, the channel described a commander “Buka Al-Araibi” killed in fighting as “one of the February field leaders, without doubt.” The commander he was referring to was among figures operating in Benghazi at a time when several armed factions in the city were later linked by international authorities to jihadist networks, including groups associated with Al-Qaeda and, in later stages of the conflict, Islamic State fighters.

When Extremists Spoke Live On Air

The channel also aired appearances by figures associated with armed groups operating in eastern Libya. Among them was Mohamed al-Zahawi of Ansar al-Sharia, who told viewers the group would not abandon its weapons until “the project of the revolution is completed.” Footage from another broadcast showed a gathering introducing the organisation and calling for “the implementation of Islamic law on this land.”

Ansar al-Sharia, whose leaders appeared in the broadcasts, was later designated a terrorist organisation by the United States, and American investigators identified members of the group among those involved in the 2012 attack on the U.S. diplomatic compound in Benghazi. At the time, the organisation’s statements and interviews were carried on the channel’s programming as part of its regular coverage of developments in the city.

Additional commentary discussed the use of car bombs and suicide attacks in the conflict, describing those carrying them out as fighters whose operations could affect the course of the battle.

The Man Behind the Channel

Al-Lafi served as the network’s general manager during the period in which these broadcasts were aired, placing him in charge of the station’s editorial output at the time.

Years after the period covered by the broadcasts, references to the same factions resurfaced in political discussions in Tripoli.

In a recorded meeting, Prime Minister Abdulhamid Dbeibah addressed individuals identified as linked to the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council and spoke about communication with officials inside the government, saying that “Walid conveys your voice to us and communicates it faithfully.” He added that arrangements had been discussed to address their situation and reopen support channels, referring to contacts maintained since the early stages of the crisis.

The exchange suggested that figures associated with the conflict period continued to have a line of communication with authorities in the capital years after the fighting in Benghazi.

Across the Diplomatic Table

Today, al-Lafi serves as Libya’s Minister of State for Communication and Political Affairs in the Tripoli-based Government of National Unity. In that role, he has participated in diplomatic engagements with international officials, including talks with the United Nations envoy and meetings with foreign representatives. In July 2025, he took part in discussions with Masad Boulos, an adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump, on political and economic cooperation between the two countries.

The overlap highlights an unresolved question that has lingered since the conflict: how governments navigate engagement with present-day officials whose past roles unfolded within the same environment in which the attack was planned and carried out? Terrorists must be held accountable. So do those who carried water for them, and broadcast it live.