Libya has once again become a critical crossroads for migrants and asylum seekers trying to reach Europe. Its vast deserts, stretching across the northeastern edge of the Sahara, mark the final African frontier for those escaping war, repression, and poverty in search of safety and opportunity across the Mediterranean.

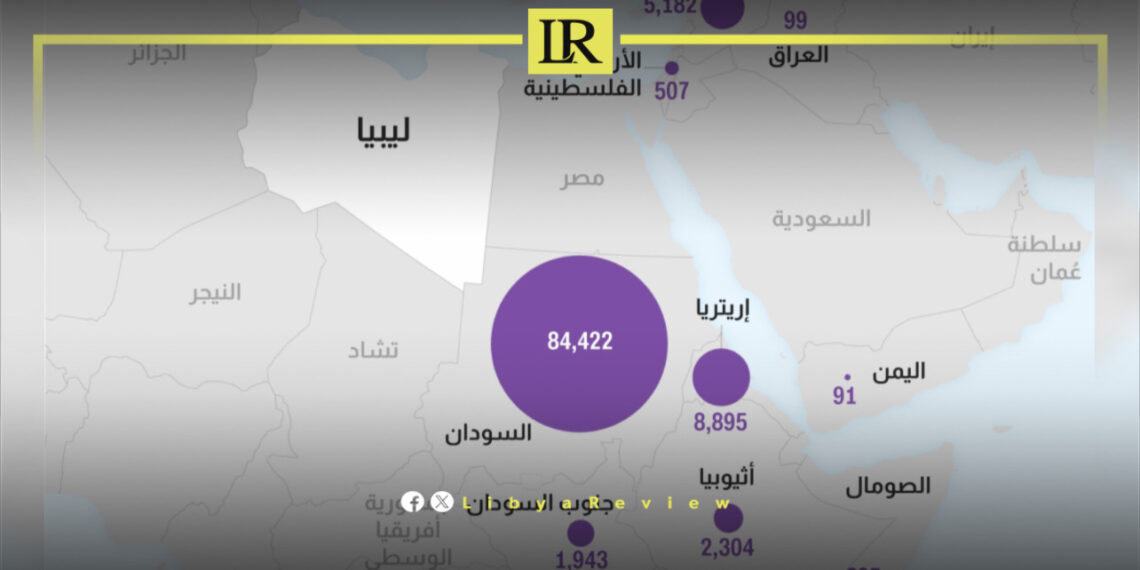

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), more than 100,000 refugees and asylum seekers are currently registered in Libya — though the actual number is believed to be far higher, as the agency operates only in areas under the internationally recognized government in western Libya.

The largest share of new arrivals now comes from Sudan, followed by Eritrea. The ongoing civil war in Sudan, which has displaced millions since April 2023, has driven tens of thousands northward through Chad and into Libya. Many flee bombings, famine, and militia violence, only to encounter new dangers on Libyan soil.

Eritreans make up the second-largest refugee population in Libya. They flee one of the world’s most repressive regimes, where indefinite military service and lack of freedoms push thousands to risk their lives each year. Often isolated and undocumented, many fall prey to traffickers who exploit their vulnerability through extortion, forced labor, or ransom schemes.

The human smuggling industry in Libya is deeply entrenched and lucrative. Migrants pay hundreds of dollars for passage through the desert and onto overcrowded rubber boats bound for Europe — if they make it that far. Payments are often funneled through the informal “hawala” network, a cash-based transfer system nearly impossible to trace.

Human rights groups continue to report abuses inside Libyan detention centers, including violence and exploitation by the Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM). UN experts say some migrants freed during raids were later abused again, while officials in Tripoli deny the claims, calling them “unsubstantiated.”

As migration from Libya intensifies, crossings toward Greece and Italy have more than tripled over the past year. Eritreans now make up the second-largest national group arriving in Italy, surpassed only by migrants from Bangladesh — a reflection of how conflict and despair continue to fuel one of the world’s most perilous migration routes.