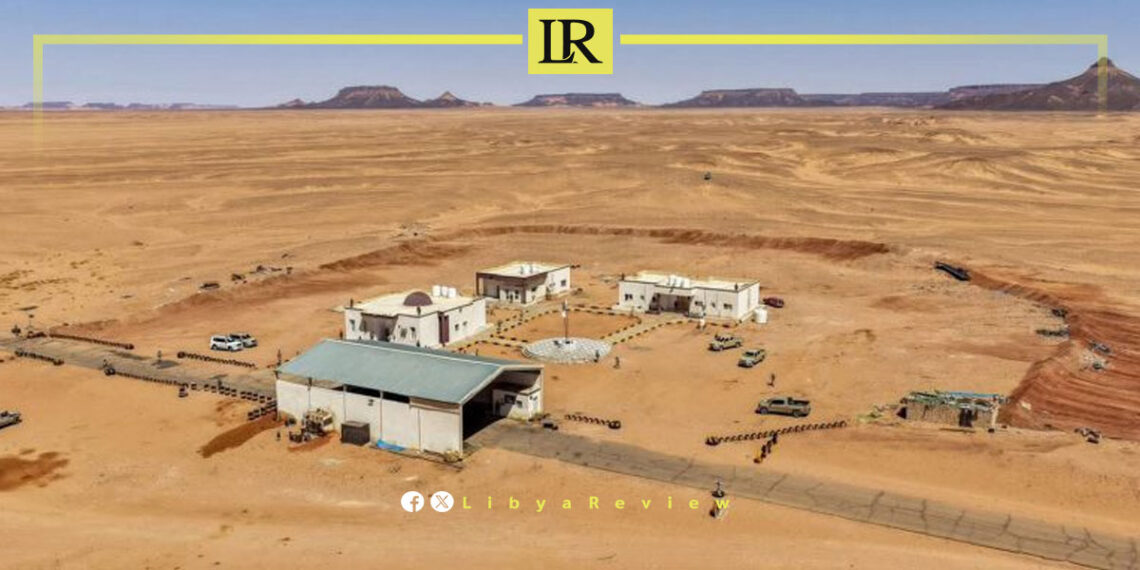

A recent armed attack on the Al-Toum border crossing in Libya’s far southwest has once again drawn attention to the fragile security landscape of the country’s southern regions and to armed groups commonly labeled as the “Southern Revolutionaries.”

The incident began when a group calling itself “Tebu Revolutionaries” launched a surprise assault on the crossing near the Niger border, briefly taking control and claiming to have captured fighters affiliated with forces of the Libyan National Army (LNA), headed by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar.

Although the LNA General Command later announced that the crossing had been retaken, the attack exposed the persistent volatility of Libya’s southern frontier.

Security sources familiar with the region stress that the term “Southern Revolutionaries” does not refer to a formal organization or a unified armed movement. Rather, it is a loose media description applied to armed elements, many of them from the Tebu community, who operate across sparsely governed desert areas.

These fighters are largely Libyan nationals, but their tribal and social ties extend across borders into Chad and Niger, allowing them to move easily through remote areas where state authority is limited.

In a video released after the attack, a spokesperson for the group described the operation as a targeted strike against what he called corruption and smuggling networks in southern Libya.

The group accused security forces aligned with Haftar of facilitating fuel and goods smuggling and warned that vehicles and checkpoints allegedly involved in such activities would be attacked or destroyed. The message suggested that the group’s objective was not to hold territory, but to send a warning and inflict material and symbolic damage.

International reports have long documented the presence of Chadian armed opposition groups in southern Libya, including factions that have used Libyan territory as a rear base during periods of instability.

While there is no evidence of a direct command relationship between these groups and the so-called Southern Revolutionaries, analysts note overlapping tribal links and occasional tactical coordination within the broader Libya–Chad–Niger border zone.

During the 2019–2020 conflict, some southern armed elements aligned temporarily with Haftar’s forces, but these alliances were largely pragmatic and collapsed as political and military dynamics shifted. The Al-Toum attack followed a familiar guerrilla pattern: a rapid assault, destruction of equipment, and swift withdrawal.

Without a comprehensive political and security approach that addresses long-standing grievances, border governance, and economic marginalization, southern Libya is likely to remain a hotspot for intermittent violence and armed mobilization.