Libya remains fraught with danger as hundreds of deadly landmines and unexploded ordnance continue to litter the landscape after years of brutal conflict. These remnants of war pose a persistent threat to civilians, particularly children, long after the battles have ceased.

“It’s a disaster zone,” lamented Saleh Farhat, whose son Mohamed is currently in intensive care in Tripoli after suffering severe injuries from an explosion. The southern outskirts of the capital, where Farhat resides, are particularly hazardous.

Despite a return to relative calm in the oil-rich nation since the battle for Tripoli four years ago, the United Nations reports that more than 400 people, including 26 children, have been injured or killed since 2019 due to leftover explosive devices.

Mohamed Farhat, ten, was playing with friends in a garden when they found what they thought was a piece of scrap metal. “A few seconds later, a strong explosion threw us to the ground,” recalled his friend Hamam Saqer, 12, who was also injured and now lies in a nearby hospital bed. “We didn’t know it was a weapon,” he added, vowing never to return to that garden again.

Libya is still grappling with the aftermath of years of war and chaos following the 2011 overthrow of long-time dictator Muammar Gadhafi. Clashes between rival armed groups have been frequent, leaving the country divided between the Trioli-based government, led by Abdulhamid Dbaiba, and a rival administration in the east.

The full extent of landmine contamination and explosive remnants of war in Libya remains unknown, largely due to the limited control of the Tripoli-based government. The southern suburbs of Tripoli, where the recent injuries occurred, have been a battleground since 2011.

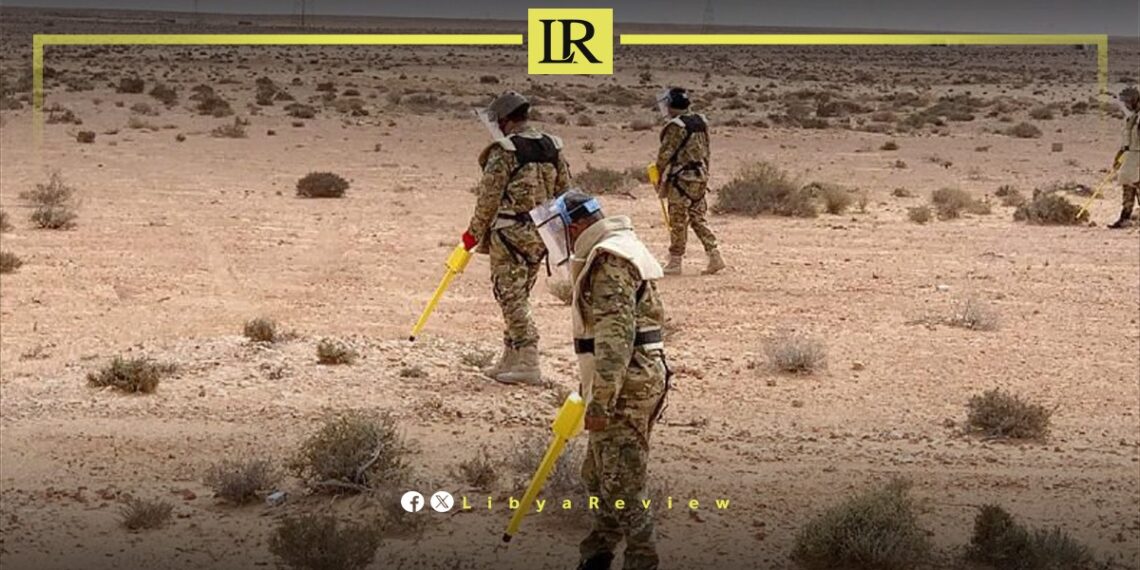

“The authorities are not doing enough to eliminate mines and unexploded ordnance,” said Farhat, who has heard numerous accounts of neighbors losing limbs due to landmines. About 36 percent of Libya’s mined areas have been cleared, according to the UN mission in Libya, but another 436 million square kilometers remain unswept.

Should Libya achieve stability and a united government, it could still take “five to ten years” to clear the remaining unexploded ordnance, an unnamed official from the defense ministry told AFP. In early May, the authorities and the Libyan Mine Action Centre announced the development of a “national anti-mine strategy” with assistance from the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian De-mining.

“People are afraid because their lives are in danger,” said Seddik al-Abassi, a local official in Tripoli, emphasizing the need for specialized equipment to sweep residential areas.

While efforts are being made to address the issue, they come too late for Mohamed Farhat. Wounded in the head by shrapnel from the blast, he is in stable condition but faces a long road to recovery.