On Sunday, a new scientific study confirmed the presence of radioactive dust over Libya, raising serious concerns about long-term environmental and health risks.

The research, led by French scientists from Paris-Saclay University, detected radioactive isotopes in Saharan dust carried by winds from North Africa to Europe. The findings, published in Science Advances, link this contamination to nuclear tests conducted by France in the Algerian desert between 1960 and 1966.

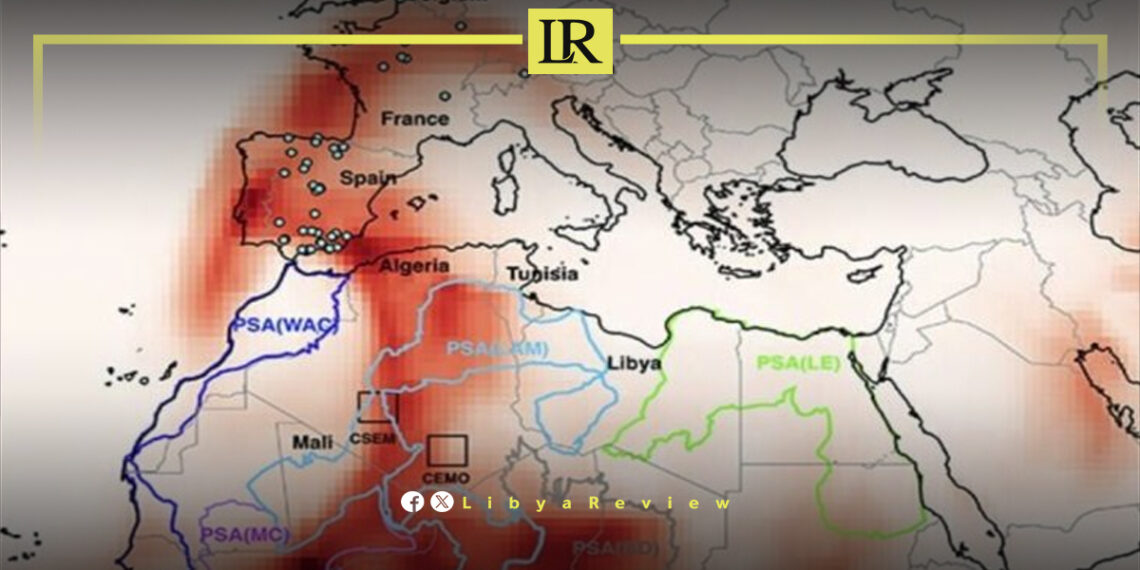

Scientists analyzed dust storms that swept across Europe between 2022 and 2024, collecting over 100 samples from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Spain. Laboratory tests found traces of cesium-137, plutonium-239, and plutonium-240.

While some radiation originated from Cold War-era U.S. and Soviet tests, a significant portion was directly linked to French nuclear explosions in Algeria.

Libya lies in the path of Saharan dust storms, making it highly vulnerable to this contamination. According to the study, the Sahara releases between 400 and 2,200 teragrams of dust annually, carrying pollutants and radioactive particles.

Around 12% of this dust reaches Europe, meaning the concentration over North Africa, including Libya, is far higher. Unlike European countries that monitor radiation exposure, Libya lacks the infrastructure to track or mitigate the impact of airborne radioactive particles.

French nuclear tests in Algeria, known as “Blue Jerboa,” “White Jerboa,” “Red Jerboa,” and “Green Jerboa,” caused widespread contamination across the Sahara.

Although France claimed these tests were conducted in uninhabited areas, thousands of people suffered from radiation-related illnesses, including cancer, blindness, and birth defects. The fallout extended beyond Algeria, spreading to Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco through desert winds.

For decades, France has faced criticism for failing to clean up its nuclear test sites in North Africa. Algerian officials have repeatedly demanded that France take responsibility for the lingering radioactive contamination. French researcher Bruno Barillot previously revealed that 42,000 Algerians, including prisoners, were used as human test subjects during nuclear detonations.

His research estimated that at least 60,000 people died from radiation exposure between 1960 and 1966.

Libya, already dealing with pollution from oil extraction and ongoing political instability, now faces additional environmental threats from radioactive dust.

The long-term impact on public health, agriculture, and water resources remains unknown. With no radiation monitoring system in place, Libya is left exposed to a silent but persistent danger.

The discovery of radioactive dust highlights the lasting consequences of nuclear tests conducted decades ago.

While Europe has the means to track and study radiation exposure, Libya and other North African nations remain unprotected. Without urgent action, radioactive particles will continue to circulate, posing serious risks for future generations.